he Camel Barn Library

Tuesday, September 28, 2010

An email from a ghost: Part II

So, there I was, 3 weeks ago, with my shiny new notebook and a blue Pilot 0.5mm fine point pen, but not exactly sure what, if anything, I was going to do with them. I had no real idea whether Project Paraschos would actually turn into something justifying the acquisition of new stationery items, or if my newly-commenced quest to find the location of the ancestral home of the Paraschos family ( formerly of Ayvalik, now of Boston and Athens) was going to end in a ruin full of feral cats, a newly concreted car park (of which there are many in Ayvalik, on the sites of old houses) or a complete dead end.

I walked down town to meet my friend Erkan -

(We are getting ahead of ourselves here, because Erkan is an important person in the story of the Camel Barn Library, which I am writing here chronologically, and needs to be introduced to you properly. But this is a real time addition to the story, so he is popping up out of sequence. Never mind. He will make his scheduled entrance in the narrative very soon. He is an interesting bloke, who has had a quite extraordinary life.)

- in a cafe by the sea, located in one of the most famous buildings in Ayvalik, at the end of a line of neoclassical facades on the water’s edge which constitute one of Ayvalik’s iconic images, frequently displayed on postcards, tourist memorabilia, or illustrating writing about the town, as above.

I was quite excited, as I walked into the cafe and saw Erkan waiting for me, because I thought my idea about finding the Paraschos house through census data was going to be a winner. I am familiar with population censuses, as they are part of my field of academic interest, and that morning had done a little research on censuses carried out during the time of the Ottoman Empire.

Censuses were first conducted in the Ottoman Empire, as they were in England, during the first half of the 19th century. The first modern census took place in 1828/29 in both the European and Anatolian parts of the Ottoman Empire. Its main purpose was to provide quantitative data to facilitate the levying of personal taxes on non-Muslims, and the conscription of Muslim male adults into the army.

In the 1830s the Ottoman government established the Office of Population Registers (Ceride-i Nüfus Nezareti) as part of the Ministry of Interior, and censuses in various different forms were conducted at irregular intervals until the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. The last one took place in 1905, and this was where I hoped to find the information we were looking for, not in the published data giving the macro view of the census, but in the detailed unpublished census data in which, as in the British censuses, individuals are located to street addresses; each person’s name is recorded against the exact address at which they live.

Unpublished census data in the UK from 100 years ago and before is now available on the internet via the National Archive, and is searchable by name and location. I have done some genealogical research on my own family using these databases, and it was remarkably easy. I didn’t really expect to find that the entire final Ottoman Empire census of 1905 would be available at the click of a mouse – this is Turkey, after all – but was hopeful that if we could get access to the unpublished census data for Ayvalik, a relatively small town, somewhere in those data we should be able to find, if we looked hard enough, the street and house number of the Paraschos family house.

I bounced into the cafe, ordered a glass of çay (tea), and related to Erkan both The Story So Far, and my idea for finding the Paraschos house using census data. What did he think?

Even before he opened his mouth, the expression was on Erkan’s face was not encouraging. Why?

‘You’re forgetting the language’ he said.

‘What do you mean, the language?’

‘Everything written during the time of the Ottoman Empire was in Ottoman Turkish. I couldn’t read it. Nor could you.’

My heart sank. In my excitement about the census idea, I had completely forgotten one very important fact: that one of the many sharp disjunctions between the Ottoman Empire of before, and the Turkish Republic of now, is in language. The modernisation of the Turkish language was one of the many fundamental reforms instituted by Mustafa Kemal, later Ataturk, the father of modern Turkey, as he separated the squalling infant of the new Turkish Republic from its dying progenitor, the Ottoman Empire.

You may be wondering how a language can suddenly be modernised out of all recognition without the entire population becoming extremely confused, and why anyone should wish to do such a thing, so let us digress for a moment into the history of the Turkish language.

During the six centuries of the Ottoman Empire’s existence the Turkish language used within its borders developed into two distinct variants, with different uses: first, there was the simpler, purer, vernacular form of Turkish, ‘kaba Türkçe’ or ‘rough Turkish’ spoken by the lower echelons of society, which remained close to the original form of Turkish brought into Anatolia from Central Asia by nomadic Turkic tribes in the late Middle Ages, namely Oğuz ( Oghuz) Turkish.

Second, following the adoption of Islam in 950 AD, and in tandem with the growth of the initially small Ottoman principality into an empire, there developed Ottoman Turkish, which eventually became the literary and administrative language of the Ottoman Empire, in particular between the 16th and 19th centuries.

Via the Persians, who introduced them to Islam, the Turks were influenced by Arabic, the language of the Koran. This, plus the fact that the Arabs and Persians were then advanced in science and literature, led the Turks to adopt the Arabic alphabet, although not its grammar. Ottoman Turkish thus came to contain a vast amount of loan words imported from Arabic and Persian, was written in a variant of the Perso-Arabic script, and was an elaborate, ornamented, rhetorical language, in large part unintelligible to the mostly illiterate majority of the population, who spoke vernacular Turkish: Ottoman Turkish was used by only about 9 percent of the population.

And this is what it looked like…

In an earlier post we discussed the triune nature of the human brain, with its newer, reasoning part, the neo-cortex, welded awkwardly on to its older, much more primitive parts, the limbic and reptile brains, and concluded that if you were if you were setting out to design a brain for a thinking being, it certainly wouldn’t be constructed like this.

Ottoman Turkish was the linguistic equivalent of the human brain: a language welded together from quite disparate parts which did not function well together, and challenging to use, even for those who were well acquainted with it. Trying to combine Turkish , Persian and Arabic together in one language was really never a good plan: the grammar and morphology of the three languages were quite at odds with one another.

As the multi-cultural Ottoman Empire declined, and there developed in Anatolia a strong movement towards an ur-Turkishness, and a Turkish nationalism which would culminate in a modern Turkish republic which expelled ‘foreign’ minorities, the strange hybrid language of Ottoman Turkish became a symbol of what needed to be left behind, and the momentum grew for the language to be reformed into something truer to its original old Turkish roots, and more accessible to the wider population.

There were early attempts to get language reform under way in the late 19thC, but the major change came a few years after the founding of the new Turkish Republic in 1923, when Atatürk instigated the great language reform. This had two major parts: one was the elimination of Arabic and Persian words from the language, and their replacement with words from old Turkish and, if necessary, neologisms based on old Turkish roots.

The Turkish Language Society was set up to bring back into use authentic Turkish words discovered in linguistic surveys and research, and its work continues to this day. The outcome of these linguistic reforms, according to the Turkish Ministry of Culture, is that the use of authentic Turkish words in written texts has risen from 35-40 percent in 1932, to 75-80 percent in recent years.

The other part of the reform was changing the script in which Turkish was written from the Arabic alphabet to the Roman, adapted with a few extra letters to accommodate Turkish vowel sounds. Atatürk strongly believed that for Turkey to become a modern state, a contemporary civilisation, it was essential to benefit from Western culture. The change to the Roman alphabet in 1928, which allied Turkish with European rather than Oriental languages, was thus a deliberate and highly symbolic act, one of the key points in his extraordinarily comprehensive programme of political, social and cultural reforms (of which we will discuss other aspects in due course), which dragged Turkey into the modern world, laying the foundations for the successful modern state which exists today.

Atatürk himself promoted the change by touring the country to introduce the new alphabet to the public, as in the photograph below, taken in Sinop -

- and public education centers opened throughout the country, resulting in a dramatic increase in literacy, which before the language reform was about 9%. By 1950, literacy rates had risen to 48.4% among males and 20.7% among females.

All exciting and important stuff, but what the language reform also did was to cut modern Turkey off, suddenly and sharply, from direct access to its written past, from the extensive written records of the Ottoman Empire, from its literature, and from its recent history. Atatürk gave a famous speech in Ottoman Turkish to the youth of the nation in 1920, one that is still compulsory reading for all Turkish school-children, but in its original version the speech is now unintelligible to the reader of modern Turkish, even if transliterated into Roman script.

Every couple of decades Atatürk’s speech has to be retranslated, so that succeeding generations can understand it. The language has changed, and is continuing to change, that much. By analogy, imagine if the English language had changed so much that Winston Churchill’s ‘Blood, sweat and tears’ speech of 1940 had to be periodically updated with new vocabulary so that we could continue to understand it. For a young Turkish person now, trying to read the original text of Ataturk’s speech would be like an English person trying to read Anglo Saxon.

And, returning to our subject after a considerable detour, the same problem would arise in trying to read Ottoman census records. As soon as Erkan mentioned the language problem, I realised that my plan was doomed: it would be impossible without the assistance of a scholar of Ottoman Turkish. And the chances of finding in Ayvalik an Ottoman Turkish scholar who would be prepared to go through the town’s entire census records to find the name ‘Paraschos’, just for fun, seemed vanishingly small.

Erkan then put an end to the whole idea by explaining that anyway, all records in Ottoman Turkish were now held in a national archive in Ankara, so we wouldn’t even be able to access them without making a 400 mile trip.

‘Oh, BUGGER’ I said. ‘Well, that’s that, then.’

We ordered some more tea, and I tried to regroup. Time to move on to Plan B, which was to go to the local property records office, and look at records from pre-1922 which would …… yes, which would also be written in Ottoman Turkish.

Plan B was then disposed of even more swiftly than plan A, as Erkan explained that current property records here only go back to the early 1930s, when the houses of Ayvalik were registered, with their new owners, in modern Turkish; all the older records were also in the national archive in Ankara.

Project Paraschos was turning out to be much more difficult than I had anticipated. There seemed to be no way forward without some more information, some clue, from the Paraschos family itself. Manny had told me he was searching through his late father’s papers to see if he could find any more information, and it was thought that his elderly aunt, who was away from home at the moment, might have a photograph of the house.

I mentioned the possible existence of a photograph to Erkan who is, amongst other things, an estate agent. His face brightened.

‘That would be much, much easier.’ he said.

‘I know every street, every house in this town. If they send a photo, and the house is still standing, I’ll be able to find it. I promise you.’

I agreed to keep him updated on any developments, went home and sat down at my computer to send Manny an email telling him of the disappointing outcome of my first attempt to find the house. When I opened my inbox, I saw that there was a new email waiting there for me from Manny. Even without opening it, I could see that there was an attachment to the email. A photograph.

I opened up the email and began to read.

(to be continued)

Monday, September 13, 2010

An email from a ghost

Exactly a month ago I received an email from a man in America. The email opened without salutation: the writer merely said that he loved my blog, and was passing it on to others, a statement guaranteed to make me feel warmly towards him, whoever he might be. He then went on to say ‘I need some information you might know something about’.

What, I wondered, might that be?

The next paragraph made my jaw drop: I was stunned.

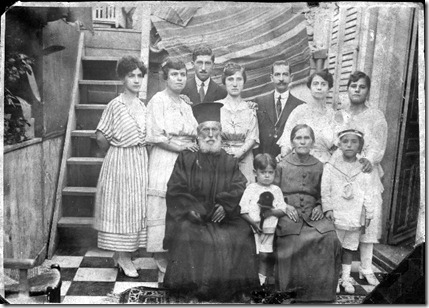

‘My father's family was from Aivali. His father was a physician at the hospital there. Is there a way to find out where the Emmanouil Paraschos (Εμμανουήλ Παράσχος) family lived until 1922?’I live in a town full of ghosts. The Greeks who lived here until 1922 hover constantly at the edge of one’s vision, a shadow population peering from the empty windows of ruined houses, and only ever glimpsed in the few photographs that remain of life here a hundred years ago: middle class couples, like the one above, in a formal pose for the photographer, confident of their place in the world; families in their Sunday best ready to attend mass at the Greek Orthodox churches that now have minarets attached;

children lining up in solemn-faced rows for school photographs;

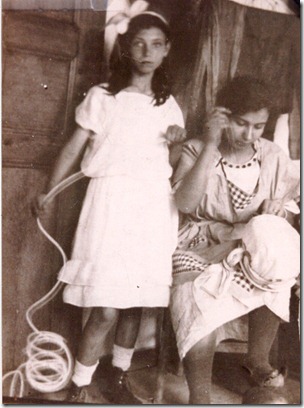

and a young girl in a white dress, gazing calmly into the future, unaware that her childhood was about to come to an end and that her adult life, if she survived the coming catastrophe, would be lived in another country:

The disjunction between those sad spectres of the past and the town in which I live has always seemed complete; when I talk to people who live here now about their family backgrounds, they tell me that their grandparents and great grandparents came here from Salonika, or Mytilene, or Crete. There is literally no one in Ayvalik today whose ancestors were here before 1923. They are gone, lost to history, and can never come back.

Yet when I read the email from the professor in Boston, a man called Manny Paraschos named, it seemed, for his grandfather, it was as if someone had suddenly stepped straight out of one of those old photographs, waving, and shouting ‘Hey! We’re still here!’

I had received an email from a ghost.

When I started writing this blog, I imagined its possible readers as people like me: interested in, but largely ignorant of, both modern Turkey and the many previous civilisations and empires which rose and fell, flourished and faded, during the last 9,000 thousand years in Asia Minor. It simply never occurred to me that the blog would be read by anyone in the diaspora of Asia Minor Greeks.

I wrote back to the professor immediately, expressing my delight at making a connection to someone now living who had his roots in that lost world, and offering to help him in any way I could in the quest to identify his ancestral home. If he had no address for the Paraschos family house, as was implied by his question, then I would try to approach the problem from another angle: I knew that population censuses list the names of all the people living at any given address, so if there were any pre-1922 census records for Ayvalik still extant, I could search them to find any mention of the name ‘Paraschos’.

Another possibility might be the Property Records Office of the Ayvalik municipality. My own house was built in 1908, only 14 years before the Greeks left, so I imagined it might only ever have been occupied by one family, and I remembered a friend telling me that if I wanted to find out who used to live in my house, I might be able to do so at the Property Records Office, where the land registration deed should record the name of the house’s first owner. Without an address, it would be more difficult, but it was possible that the details from land deeds had been computerised, and one might be able to search by name, rather than address.

I outlined these possibilities, both of which seemed to offer at least some slim chance of success, to Manny, and undertook to discuss the problem with a Turkish friend here, who has a strong interest in, and considerable knowledge of, local history. However, not wishing to get his hopes up too high, I added the following caveat: that many records had been destroyed during the cataclysmic events in Anatolia between 1919 and 1923, and that even if we could manage to find the address where the Paraschos family lived, the house might be a ruin, or have disappeared completely and been replaced by a new building. I would do my best to help him find his family home, but was, in truth, doubtful of a successful outcome.

Still, it was a fascinating quest, and I was determined to try. I arranged to have lunch the next day with the friend who might be able to advise me on my search, and bought a new notebook, on the basis that all great –or even small – enterprises should begin with a new notebook and a Pilot pen with a very, very fine point.

Project Paraschos was now officially underway.

(to be continued)

Wednesday, August 25, 2010

My City of Ruins

“Those who take pleasure in the accidental beauty of poverty and historical decay, those of us who see the picturesque in ruins — invariably, we’re people who come from the outside”.If you come from one of the tidier countries of northern Europe, like the UK, then you will spend the first couple of days of your first visit to Ayvalik in a state of shock. The guidebooks will have told you of the charm of the town’s cobbled streets, lined with picturesque old Ottoman Greek houses, and you may well have had your appetite further whetted by the ‘Rough Guide to Turkey’ rhapsodising thus:

Orhan Pamuk '’Istanbul: Memories and the City’

‘Ayvalik presents the spectacle –almost unique in the Aegean – of an almost perfectly preserved Ottoman Greek market town, its essential nature little changed despite the inroads of commercialization. Riotously painted horse-carts clatter through the cobbled bazaar, past the occasional bakery boy roaming the alleys in the early morning selling fresh bread and cakes….Well, yes -

There’s little point in asking directions: use the minarets as landmarks and give yourself over to the pleasure of wandering under numerous wrought-iron window grilles and past ornately carved doorways.’

- a whole book could be devoted solely to the eccentric beauty of the doorways and wrought iron work of Ayvalik .

But what they don’t tell you about is the ruins.

In an earlier post I described how in September 1922 the Orthodox Greek inhabitants of Ayvalik were forced to leave the town and migrate to Greece, taking with them only what they could carry, and how they were replaced a year later by Muslims forced to migrate in the other direction, from Greece to Turkey, who moved into the abandoned houses of those who had left, and turned their churches into mosques.

The incoming migrants, however, were much fewer in number than those who were forced to leave, which meant that a lot of houses were left empty. Some of them have remained uninhabited to this day, and have been standing there, slowly decaying, for the last 88 years. This process was accelerated by an earthquake during the 1940s, during which some of the taller, three- storied houses lost their upper floors. As a result, the charming cobbled streets of Ayvalik feature - amongst the moderate number of houses that have been properly restored and the rather larger number that have been modernised in what is perhaps best described as an ad hoc fashion – many houses in various stages of decay and ruin, some long beyond the hope of repair.

My street contains several beautifully restored houses, amongst them the elegant summer residence of one of Turkey’s most famous rock stars (the house and its restoration have been featured in newspaper and magazine articles in Turkey, so its location is well known):

It also, in rather marked contrast, contains this

and, right next door to me, this:

The ruins are beautiful in a heartbreaking kind of way: you will see a huge, imposing doorway (Ayvalik is full of doorways with attitude), a magnificent facade, and behind it nothing…

…but the bare bones of the house it was once was.

Houses fall down regularly in Ayvalik, despite the fact that the old town is a conservation area, and has been for decades; a friend of mine narrowly missed being hit by the falling rubble when the house pictured below collapsed a few months ago:

To someone coming from a country whose architectural heritage is preserved, conserved, restored and polished to the nth degree, such a state of affairs is, at first, literally incomprehensible. The first-time British visitor wanders about the old town of Ayvalik dazed and confused: delighted by the beauty of the town, but simultaneously quite overwhelmed by the stunning visual impact of its decay.

It takes a bit of getting used to.

Once coherent thought returns, the visitor’s next reaction is ‘But this is terrible! How can such a thing be allowed to happen?’ to which the short answer is ‘Burası Türkiye’ – a popular phrase meaning ‘This is Turkey.’ The longer answer, inevitably, comes under the category of ‘It’s complicated’, and I’m not sure that I can provide an adequate explanation. However, the answer seems to lie in a complex tangle of cultural, political and economic factors.

One view, put forward by Bruce Clark in 'Twice A Stranger' his book about the 1923 Population Exchange between Turkey and Greece, is that for painful historical reasons there is no particular general desire here to preserve the architectural heritage, however picturesque, left behind by what are perceived as the historic enemies of the emergence of the Turkish nation state, the Asia Minor Greeks (with a mirror image of this sad situation being found vis-à-vis the many physical remains – and thus reminders - of centuries of Ottoman rule in what is now Greece).

A Turkish friend of mine here in Ayvalik argues against this view, pointing out that the problem of preserving the physical remains of Turkey’s multiply layered multicultural heritage is a much broader one, and I would tend to agree. As described previously, Turkey is chock full, on a scale quite difficult to comprehend, of the archaeological and architectural remains of earlier civilisations (and I will list them again, as I do so love the litany of their names) -

Hattis, Hittites and Hourrites, Uruartians, Phrygians and Lydians, Assyrians, Persians, Greeks and Trojans, Romans, Byzantines, Selcuks and Ottomans

- amongst others. Many of these sites have never been excavated, and perhaps never will be, because there simply isn’t enough money, in a country which is still developing, so from this point of view a few crumbling Ottoman Greek houses in a small town in the north west Aegean are perhaps fairly minor in the great Anatolian scheme of things.

There is a wider cultural point, however, which seems significant: Turks, on the whole, are not that interested in old houses, and with a few exceptions have little interest in restoring them, much less living in them. This is a sweeping generalisation, but there is empirical evidence to support it. To explain why this is the case we need to take a brief look at the development of Ottoman architecture (Ottoman referring to the period between 1299, when the Ottomans took over in Anatolia from the Seljuk Sultanate of Rūm, and 1923, when the Ottoman Empire officially ended and the Turkish Republic was established).

Stephane Yerasimos, an architectural historian specialising in the Ottoman era, describes how Turkish domestic architecture developed using a material – wood - chosen for its transience, with the spiritual symbolism that entailed, in contrast to the permanence of the stone used for public buildings:

'The need to emphasise the transitory character of human life, in every undertaking related thereto, became a fundamental principle of Ottoman civilization, especially in the synthesis it effected between architectural creation and its materials. By contrast with the mosque and other public buildings (caravanserais, baths, hospices etc) , designed to endure and thus fashioned of stone for all eternity, the structures for sheltering the private lives of individuals are in wood, made to be rebuilt from one generation to the next.’The high density and proximity of the wooden houses of Istanbul and other Ottoman cities led to repeated destruction by fire, and gave a wood-built house a life expectancy of only thirty years or so; as a result, the constant replacement of domestic living spaces, generation upon generation, has been a feature of Turkish life for hundreds of years.

Stefane Yerasimos, ‘Living in Turkey’

It is instructive in this context to consider what has happened during the last hundred years to the wooden houses of Istanbul, the main component of the city’s domestic architecture since the 16th century.

Their fate has some parallels to the situation in Ayvalik. At the beginning of the 20th century most of Istanbul's housing stock consisted of wooden houses. Today, there are only about 250 timber houses left in the entire city, and many of them are in a very poor state of repair.

For four hundred years, wooden houses were built, and regularly replaced, generation after generation. But after particularly devastating fires during World War One, construction in wood was banned by the authorities. The wooden houses could no longer be replaced, and throughout the twentieth century those remaining have fallen victim to neglect, poor planning, and population changes.

Most of the tradesmen who had the skills to maintain and restore these houses were from the Greek and Armenian ethnic minorities who vanished from Anatolia, through death or deportation, during the cataclysmic events of the first two decades of the twentieth century. After the Second World War the Turkish middle classes abandoned the neighbourhoods of decaying wooden houses for more modern suburbs, leaving the old houses to rural immigrants without the money, or the know-how, to repair and maintain them. Although the planning laws in theory protected the houses, as in Ayvalik, many have been allowed or even encouraged to fall down by owners with no interest in preserving them, and local authorities are reluctant to spend public funds on houses in private ownership.

In Ayvalik, too, owners of old decaying houses have preferred to move to more modern accommodation in the suburbs, rather than bear the considerable financial costs of modernising and maintaining inconvenient old houses. Many of the houses in the old town of Ayvalik are now rented, to recent migrants from the east of Turkey, who, like their counterparts in Istanbul, have neither the money nor the skills to maintain the buildings.

It would be possible to obtain funds for the urban regeneration of Ayvalik from the EU, or UNESCO, as has happened in a few other places in Turkey, notably Safranbolu and Eskişehir. However, that would depend on energetic project leadership from the political leaders of the town, something that has to date been notably lacking.

The houses that have been properly restored belong mostly either to incomers from Istanbul or Ankara – Ayvalik attracts writers, artists and musicians, like my neighbour the rock star – or to foreigners, like myself. Unfortunately, there aren’t enough of them and, even more unfortunately, two years ago the Turkish government passed a law banning foreigners from buying property in Turkey in areas of ‘cultural and historical importance’; the old town of Ayvalik is one of those areas. Since there are rather more foreigners than Turks interested in buying these houses, and willing to pay the considerable costs of restoring them to the required standard, this has slowed down the rate of house restoration considerably. A few foreigners continue to buy here by having the ‘tapu’ (property deed) held by a Turkish friend, but it is something not many people are willing to consider.

It is probable that the law will be rescinded at some point, but the houses are fragile, and every winter the torrential rains, which intermittently fill the steep streets of Ayvalik with running water, further damage and destabilise these already weakened structures. At least half a dozen houses have fallen down in the two years I have been living here, and there are many others on the verge of collapse. It is immensely saddening to see the decay progressing, week on week, month on month, year on year.

The ruined houses of Ayvalik have a peculiar, haunting sadness about them. The restored and modernised houses, the lived in houses, have moved on into a new era, and are continuing to function, the horrors of what went before papered over with another layer of history. For the ruins, however, there is no such effacement of the past: they stand there empty, untouched and unlived in for nearly ninety years now, and decaying more with every winter’s rains. And their doors - if they still have doors - stand always open, waiting patiently for their lost owners to come home.

‘The sigh of History rises over ruins, not over landscapes’

Derek Walcott

Tuesday, August 10, 2010

Entertaining angels unawares

‘Her yiğidin bir yoğurt yiyişi vardır: Each man has his own style of eating yoğurt.’

Turkish proverb

A recent visitor from England, walking round the local supermarket with me, stopped in front of the chiller cabinet – actually, the series of chiller cabinets - devoted to yoğurt, and said:‘That’s interesting. In Turkish they have the almost same word for yoghurt as we do. Is that a word they’ve borrowed from English?’

I stared at him, appalled.

‘It’s a Turkish word. The Turks INVENTED yoğurt. The English stole the word from them. And MANGLED it.’

My visitor looked slightly bemused by the vehemence of my reaction, as well he might. He had no idea of the central importance of yoğurt in Turkish life and culture, although the stream of people lugging huge 5 litre BUCKETS of the stuff into their supermarket trolleys might perhaps have given him a bit of clue.

So, let’s talk about yoğurt. There are some things you really need to know.

First, spelling and pronunciation: the British, when importing the word yoğurt into the English language, came a cropper over the fact that is spelt with a silent ğ which was transliterated into English as a ‘gh’. This was fair enough, as in English, as a general rule

Vowel + g + h -- silent gh as in Dough

but it ended up being pronounced as a hard g, when it shouldn’t have been pronounced at all.

What were we thinking?

Yes, I know. I still haven’t properly explained the Turkish silent ğ. But there’s a lot to get through. There will be a post on the strangeness and difficulty of the Turkish language very soon. For now, all you need to remember is that it is an

(WARNING: do not click the following link if you suffer from any kind of Grammatical Anxiety Disorder)

agglutinative language and features a silent ğ, the use of which simply lengthens the vowel in front of it.

So it’s not yo- as in ‘But soft! What light through yonder window breaks?’ -urt (William Shakespeare)

It’s yo - as in ‘I said Yo, Jay, I can rap’ -urt (Kanye West)

So there it is: a silent ğ and a long ‘o’ – yo’urt.

The word is derived from the root yoğ- , which is the basis of a number of Turkish words relating to density, and the process of thickening or condensing: e.g. yoğun – thick, yoğunlaşmak – to become dense, thicken, or condense.

But enough with matters linguistic, before you lose interest entirely and wander off to Awfulplasticsurgery.com (No, of course I didn’t make that a hyperlink; I’m not entirely stupid. But do go there later to marvel at the bizarre juxtaposition of photos of Hollywood celebrities with surreally bad plastic surgery and … adverts for California plastic surgeons. Only in America).

Let’s get on to the more – and you’re going to have to trust me on this - interesting stuff: the history of yoğurt.

In the beginning, for thousands of years, the original Turks were nomadic tribes, roaming the steppes of Central Asia (they didn’t turn up in what is now Turkey until considerably later). They were pastoral nomads: indeed, Central Asian Turks were the first people ever to domesticate sheep and cows, during the Neolithic age. Living in a climate where summer temperatures were around 40 degrees Centigrade, and frequently travelling long distances, they needed to find ways to preserve food, particularly the milk from their herds.

At some point it was noticed that when milk fermented, it turned into a denser, slightly sour substance which stayed fresh much longer than raw milk: and thus was yoğurt invented. It was first made and stored in animal skins, easily transportable when the nomads were travelling. Exactly how long ago this happened is a matter for conjecture, but it’s likely to have been not long after the first domestication of sheep and goats in the Neolithic age, so at least 5 or 6 thousand years ago.

Perhaps yoğurt’s earliest appearance in the written historical record is in the Bible: in the Book of Genesis, (which in its current form dates back to 500BC or thereabouts) we find the famous story of Abraham putting together an impromptu al fresco meal for some strangers who arrive unexpectedly, and later turn out to be divine messengers. The menu included ‘curds (i.e.yoğurt) and milk’ – perfect for a light lunch should you find yourself ‘entertaining angels unawares’.

Another very early written reference to yoğurt comes from Pliny the Elder’s ‘Natural History’ (written around AD 77-79), in which this cheese-loving Roman imperialist, happily unaware that one day there would be yoğurt-fuelled barbarian hordes frolicking in the ruins of the Coliseum, rather snootily observes:

"It is a remarkable circumstance, that the barbarous nations which subsist on milk have been for so many ages either ignorant of the merits of cheese, or else have totally disregarded it; and yet they understand how to thicken milk and form therefrom an acrid kind of milk with a pleasant flavour".It is entirely irrelevant to the subject under discussion, but nonetheless interesting, that Pliny the Elder died during the eruption of Vesuvius which destroyed Pompeii, after sailing from a position of safety across the Bay of Naples towards the eruption, in order to study what was happening at closer quarters. Pleasingly, this self-immolation for the sake of furthering human knowledge did not go entirely unrewarded: Pliny is still remembered in volcanology, where the term Plinian refers to ‘a very violent eruption of a volcano marked by columns of smoke and ash extending high into the stratosphere’.

I’m sure Pliny would have been thrilled.

The historical significance of yoğurt to the Turks is demonstrated by the fact the word yoğurt is included, with the same meaning, in the oldest known dictionary of the Turkish language, Kasgarli Mahmut’s ‘Divân-i Lûgat’i Türk’, published in the 11th century. There is an entire thesis to be written on the role of yoğurt in Turkish epic poetry and other literature, but to gauge how important yoğurt still is in the average Turkish home, let me just point you to the following short extract from the section devoted to yoğurt on the fascinating Turkish Cultural Foundation website, a fount of information on all aspects of Turkish culture:

A dish that is to be accompanied by yoğurt is a must on any traditional Turkish table - unless of course, there is already another dish whose main ingredient is yoğurt. For thousands of years, yoğurt has been an indispensable element on Turkish tables. It is consumed plain or as a side dish, and it is a crucial part of Turkish Cuisine. Yoğurt is used to make soups, sweets, and the favorite drink ayran, which is made by mixing in water, mineral water and salt. Another reason why Turks hold yoğurt dearly is that all over the world it is consumed and known as “yogurt,” which is a word of Turkish origin.A few months ago I visited Diyarbakir, an old city in south-eastern Turkey famous for its dramatic black basalt city walls, and was delighted to find there an entire bazaar, many hundreds of years old, devoted to yoğurt - the Eski Yoğurt Pazar:

Inside, I saw where they got the idea for the plastic buckets in which yoğurt is now sold in Turkish supermarkets:

In the rural south east of Turkey, they still make and sell yoğurt the old-fashioned way, something I was to witness for myself a few days later when I went to stay with a family in a village on the Mesopotamian plain between Diyarbakir and the ancient city of Urfa (the biblical Ur, and birthplace of the yoğurt-loving Abraham).

This happened purely by chance: ready to move on from Diyarbakir, I was looking on the internet for hotels in Urfa, and came across a local company called Nomad Tours, which conducts short tours around south eastern Turkey, and also arranges home stays in Yuvacali, a remote, very poor, village some distance from Urfa. The home stays (which Nomad Tours organises on a voluntary basis) enable villagers, who make a meagre living from subsistence farming, to earn some money, and provide their guests with an insight into rural life which it would be impossible to obtain in any other way.

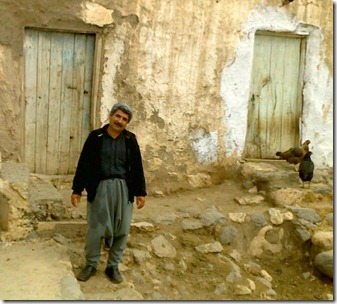

I’m going to write in more detail at a later date about the time I spent in Yuvacali, which was the highlight of a month-long solo trip exploring south-eastern Turkey for the first time. For the time being, let’s focus on the yoğurt-related elements of my stay there with my hosts Pero,

Halil,

and family:

in their partly concrete, partly mud house looking across the Mesopotamian plain to Mount Nemrut in the far, far distance, on the other side of the Euphrates:

The concept of ‘food miles’ is not really applicable in Yuvacali, where virtually everything the villagers consume (except tea) is produced on their own smallholdings: Pero and Halil grow wheat, vegetables and fruit, and raise sheep, cows and chickens, to provide eggs, meat and milk, which is made into cheese, yoğurt, butter and ayran.

Truly, Yuvacali is Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall’s spiritual home, although even he might find the stand-pipe which provides water, and the outhouse in the middle of the vegetable garden, a little challenging:

My hostess Pero, a woman for whom my admiration knows no bounds, shoulders a work load which would fell most Western women about half way through the first day, including as it does rising at dawn to sweep the farmyard, before feeding the chickens, milking the sheep and cows and cooking the day’s bread over an open fire. All this before breakfast.

But for the moment, let’s focus on the yoğurt.

You’ve probably seen yoğurt recipes before; you may even have got yourself one of those nifty little electric yoğurt-makers and brewed up at least one batch of this life-preserving superfood for yourself and your loved ones before relegating it to the back of the kitchen cupboard which houses all the gadgets that will never be used again.

You are unlikely, however, to have seen a yoğurt recipe which provides you with a step by step guide from sheep to breakfast table.

Ladies and Gentlemen, I give you:

How to Make Yoğurt in 6 Easy Steps, Yuvacali-style

Step 1: First catch your sheep

Step 2: You and the sheep, up close and personal

Step 3: Milking done, disengage from your sheep and rise gracefully in one swift movement, taking care not to allow the sheep to kick over your bucket of milk as you do so (this may require a little practice).

Step 4: Take the milk to the dairy, built with thick mud walls to withstand the baking heat of the Mesopotamian plain*

Step 5: Boil the milk, add the ‘starter’ from the previous batch of yoğurt and then leave it to ferment, a process which takes only a few hours.

Step 6: Preside over the next day’s breakfast table, with yoğurt that has travelled all of 3 yards, from the dairy into the house, and is still within spitting distance, literally, of its sheep of origin.

* Should you try to recreate this recipe in its entirety in, for example, the English Home Counties, it might be wiser to focus more on the water-proofing aspect when constructing your dairy.

******

‘Sütten ağzı yanan, yoğurdu üfleyerek yer: A man who’s burnt his mouth drinking hot milk will drink even yoğurt very carefully’.

Turkish proverb

Thursday, August 5, 2010

Alexander the Great says ‘Just do it’

In an ideal world - the world say, of many of the most important philosophers in the history of Western thought, and virtually all economists - human beings make decisions guided purely by reason, assessing carefully beforehand the likely advantages and disadvantages of any given course of action. Although there are other internal influences on human behaviour, namely emotions and desires, what distinguishes humans from animals is our power of rational thought, and that is what can, and should, prevail in human decision making.

This paradigm came down to us from Plato and Aristotle - by way of the 17th century Rationalist philosophers, Descartes, Spinoza and Leibniz, followed by Kant and the other philosophers of the Enlightenment - into the work of 20th century social scientists, especially economists, who enshrined the idea in Rational Choice Theory. This theory is based on the supposition that the ‘Rational Actor’, free of any external influences, performs a cost-benefit analysis on each and every potential course of action, and then chooses how to behave accordingly.

This model of decision-making, ubiquitous in social science is, of course, a little detached from the real world, as even economists have finally started to admit: in the last 20 years or so the advent of ‘behavioural economics’ has acknowledged the existence of ‘fuzzy’, non-rational elements also influencing human behaviour.

These non-rational elements developed at a much earlier stage of human evolution than rationality. We only have to look at the way the human brain is structured to see that rationality, which is processed by the neo-cortex, was a late addition to the human cerebral tool-kit:

Beneath the neocortex, the reasoning brain, lie the limbic and reptile brains. These are much, much older and more primitive, and provide instinctive responses governing behaviours essential to the maintenance of human life: the homeostatic physiological systems of the human body, defence, dominance and aggresion, and mating. The instinctual behaviours deriving from these older parts of the brain can, and often do, override the commands of conscious rationality.

The human brain has evolved in a fairly haphazard fashion– if you were setting out to design a brain for a thinking being, it certainly wouldn’t be constructed like this – and the rational brain has been compared to ‘an iPod built round an eight track cassette player.’ Thus, in contrast to the smooth cost-benefit calculus of the imaginary Rational Actor, the way we behave is generally a messy compromise, the outcome of the constant tension between the dictates of reason and the powerful inputs from our instinctual emotions and desires.

The subordination of rationality in human decision-making concerned with any kind of desire, corporeal or otherwise is, perhaps, summed up most neatly in Pascal’s celebrated anti-Rationalist one-liner: ‘Le coeur a ses raisons, que la raison ne connaît point’ : ‘the heart has its reasons, of which Reason knows nothing.’ Pascal and Descartes did not get on, and this remark was by way of an ‘up yours’ gesture to the man who inflicted the lingering blight of Cartesian Dualism on the world.

All bets are off, then, when it comes to the conflict between reason and passion, as was demonstrated only too vividly on my second visit to the camel barn. In a previous post I described visiting Ayvalik for the first time, seeing and falling in love with the camel barn, and buying it the next day. That is the essence of what happened, but of course it wasn’t quite as simple as that.

I went back to look at the house and barn for a second time the next morning, before making a formal offer for the property, and during that second visit both the rationality of my decision, and my sanity, were called severely into question by the friend with whom I had come to Ayvalik.

Standing in the camel barn that morning, and again overwhelmed by a passionate longing to turn this building into my long-desired library, I was assaulted by reason in the form of my Turkish friend and university colleague Tuğçe (pronounced Too-cher – we will discuss the Turkish silent "ğ" at a later date). She had brought me to Ayvalik for a weekend to see if I liked the place and might one day consider buying a house there, and was now seriously alarmed by my sudden – and, as she saw it, manifestly crazy - determination to do so immediately, only 24 hours after arrival.

Acting as the Voice of Reason in the face of my raging passion to acquire the camel barn as soon as was humanly possible, Tuğçe seemed that morning to be channeling Immanuel Kant (poster boy for Enlightenment philosophy, high priest of Pure Reason, declared enemy of passion and kill-joy extraordinaire), something quite unusual for this blonde, beautiful academic and feminist of the postmodern kind, who is normally much more likely to be found channeling her icon and look-alike, Marilyn Monroe.*

Whilst I stood, speechless , smitten, in the camel barn, with the vision of the glory of my future library before me, Tuğçe was looking round the place with an expression of marked distaste.

In retrospect, I suppose she may have had a point, but at the time I was baffled by Tuğçe’s lack of enthusiasm; the ensuing discussion, across a vast gulf of mutual incomprehension, went something like this:

T: Caroline, you should really go away and think about this for a while before making a decision.

C: I don’t need to think any more, thank you. I’ve already made my decision.

T: Caroline, this barn is just a wreck, a big empty space, a heap of old stones. The amount of work required to restore this building would be enormous. And enormously expensive.

C: It’s an empty space now, admittedly, but like all empty spaces, it has a HUGE amount of potential.

T: Shouldn’t you discuss this with your family first?

(Family is all important in Turkey. Very close family ties, and constant family togetherness, are central to Turkish culture. Taking a major financial decision like buying a house and barn would be unthinkable without lengthy discussions involving, probably, the entire extended family, including uncles and aunts. Uncles and aunts loom large in Turkish family life).

C: No, what’s it got to do with them?

T: (shaking her head) I don’t understand you English.

She then decides to come at it from another angle:

T: It will be very, very expensive to make a restoration of this building.

C: Yes, you’ve already said that.

T: For the same price, or less, you could have a lovely new villa in Şirinkent (a delightful seaside suburb of Ayvalik, where many residents of Istanbul and Ankara have summer homes) with central heating, air-conditioning and a communal pool. Low maintenance, lovely gardens, right by the sea, no restoration needed. Are you crazy?

C: I don’t want a villa, Tuğçe, I want a library.

Tuğçe sighs, heavily.

T: OK, if you really MUST have one of these high maintenance, inconvenient and uncomfortable old houses, why don’t you get one that’s already been restored? There are plenty of them for sale, and they’re not that expensive.

Then you will know how much money you’re spending up front. If you buy this… wreck and try to restore it, you have no idea what the final price is going to be.

C: We’ve already looked at some restored houses, Tuğçe, and they’re perfectly lovely, but none of them has enough room for MY LIBRARY.

T: Have you ever restored an old building before? Do you know ANYTHING about restoring old buildings?

C: No, and no. I’ve lived in some, though.

T: Do you know anything about plumbing, wiring, roofing, anything about building at all?

C: Not as such.

T: Do you know anything about Turkish building regulations? They’re very complex, especially in a conservation area like this, and the planning office bureaucracy is always difficult to deal with. It’s one of the things we inherited from the Byzantine empire.

C: I’ll find someone who does know to help me.

T: And you will communicate with this person how, exactly? To my certain knowledge you only speak 4 words of Turkish so far: merhaba, teşekkürler, and çok guzel. (hello, thank you, and very nice)

C: I’ll find someone who speaks English to help me.

T: This is not Ankara: Ayvalik is a small provincial town 170 km from the nearest city. Almost no-one here speaks good English. And the builders will cheat you because you are a foreigner. That’s a given. And you’re a foreigner who doesn’t speak Turkish, so they will cheat you more. MUCH MORE.

And you’re working 700 km away in Ankara, Caroline. How can you possibly manage a building restoration project in Ayvalik when you can only come here in the breaks in between university semesters? You will lose all your money, it will be a total disaster, and then your family will blame ME for bringing you here.

C: I think I’m beginning to sense a little negativity here, Tuğçe.

T: That’s because you’re being CRAZY. This is a crazy, irrational idea. You will regret it if you buy this place. It will bring you ALL SORTS of trouble. I’m trying to save you from yourself.

By this point I was mentally sticking my fingers in my ears and going ‘lalalalalalala I CAN’T HEAR YOU!’

Then Tuğçe went in for the kill:

T: Also, you have no practical skills whatsoever. You told me your mother spent your entire childhood trying to keep you away from sharp objects.

C: And that is relevant to this discussion how?

T: Caroline, I know you. Your brain works very well for tasks requiring abstract verbal reasoning. That’s your special skill. But you should leave building restoration projects to others. People who can successfully use scissors.

But by now Tuğçe’s voice was receding into the distance, merging with the faint squawks of the seagulls flying overhead across the Aegean towards Lesbos, just offshore.

I was lost in Library World again, and this time my vision was much more detailed.

I could see right before my eyes the bookcases in the library: vaguely Greek looking, with that neoclassical revival vibe, and all the books lined up there, finally out on shelves again after all those years stored away in boxes, and neatly divided on the shelves into sections and subsections, and properly catalogued with some of that amazing bibliographic software you can get now, which comes complete with YOUR OWN BARCODE SCANNER, and how cool is THAT?

And I could see a great big stone fireplace on the end wall, with big comfy chairs and sofas around it, and desks, and tables to put books on that you don’t need just now, but might need a little later, so you don’t have to put them back on the shelf in the interim, and lots of lamps and good reading lights, and on the 10 metre long wall of the barn opposite the main door a wooden gallery, with an iron spiral staircase going up to it, and then up on the gallery more bookcases and a small desk underneath the little window in the centre, where you would be able to sit and work and look out of the window at the giant mulberry tree that stands in the garden of the house behind the barn.

I saw all those things quite clearly, right inside my head. My very own bibliographic paradise. And all that was standing between me and the beautiful library in my head was the organisation of a little building project, just a few months’ work.

Was not the realisation of my life-long dream worth a little effort and expense?

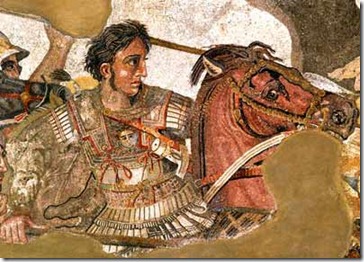

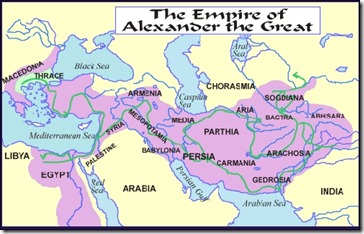

Suddenly, I thought of Alexander the Great, who swung by this part of the world a couple of thousand or so years ago and whose passage, against all the odds, was marked with a pretty substantial record of success.

I turned to Tuğçe.

C: Sometimes, Tuğçe, when you have a dream, you just have to forget about rationality and take a step into the unknown. Alexander the Great would never have got out of bed in the morning if he’d thought rationally about his prospects of success in trying to invade Asia Minor, overthrow King Darius III and take over the Persian empire, would he?

T: What ARE you talking about?

C: Really, Tuğçe, compared to conquering the entire known world between Macedonia and India, renovating a camel barn in the north Aegean should be a piece of cake.

T: (keening) Allah, Allah…

C: And let’s not get this out of proportion: I’m not going to be unravelling the Gordian knot, just renovating a couple of old stone buildings in a town where loads of other houses are already being renovated.

Really, how hard can it be?

* In order to protect Tugce’s privacy, I offered to change her name in this blog, in which she will be a frequently recurring character. This suggestion horrified her: she has opted instead for full disclosure, pictorial representation and, moreover, would like it to be known that she is currently single.

Wednesday, July 28, 2010

Street Life

The great heat of July is upon us; it is the price we pay for the glorious months of sunny, warm weather in the spring and autumn. July is the hottest month: the heat of August is always tempered by strong winds blowing from the north –‘Ayvalik air-conditioning’ – but in July, when the temperature is often in the high thirties, and occasionally the low forties, there is little relief from the heat unless you sit by the sea, or climb up the hill to the woods, in both of which places you can generally find a cooling breeze.

In the old town of Ayvalik, many of the residents are quite poor, and air conditioning units are unusual. Most of my neighbours simply have to endure the stifling heat , and during the summer months a large part of their time is spent outside, in gardens, on roof terraces and balconies, but also in the cobbled streets in front of their houses.

Many of the people here are recent migrants from villages in the east of Turkey; although now living in the town, they manage an approximation of the village life they left behind, often keeping chickens or, on the higher ground up near to the woods, a few sheep or goats.

The companionable evenings spent sitting outside on the street are a relic of village life and, as the weather gets warmer, pieces of furniture begin to creep outside to make this outdoor living more comfortable. When Freddie and I climb up the hill at 6.30 a.m to walk in the comparative cool of the very early morning, the sofas and chairs lie empty, and look a little incongruous:

In the heat of the afternoon the streets are quiet, as it is simply too hot to be outside, but with the approach of evening, as the shadows lengthen and the heat begins to abate, people start to emerge from their houses.

Soon the cobbled streets burst into life again, with children playing energetic games to work off the energy accumulated whilst cooped up inside for the afternoon; their parents, meanwhile, sit outside their houses and chat with their neighbours.

Children here spend far more time outside and have infinitely more freedom than in England; whenever I feel slightly irritated at the foghorn cries of the little boys who play football in my street, I remind myself that this is what little boys are meant to do.

Hilary Clinton’s dictum that ‘It takes a village’ to raise a child can be seen in action here: even very small children play outside in the streets unsupervised, as there is always a neighbour around to watch out for them, and few strangers wander around in the cobbled streets and alleys that wind their way up the hill in the old town.

By the time Freddie and I return from our evening, walk, around sunset, the sofas and the front doorsteps are fully occupied:

When you walk a dog every day along a regular route, you become part of people’s mental furniture. They look out for you, exchange greetings, express concern if you have failed to appear for a few days and gradually, although you don’t really know each other, you become friends of a kind.

The woman in the photograph above is called Sardya, although I'm not sure if that's exactly how you spell it. She sits outside her house every evening in the spring and summer, when the weather is good. Freddie and I have to climb up a very long, very steep flight of steps to get up to the street where she lives, which leads straight up the hill into the woods. One day, seeing me breathless after the climb, Sardya motioned to me sit down and catch my breath, and we talked for a while.

Now we have become friends, across the gulf of culture, language, age and experience that separates us. Sardya has a kind of tranquil beauty which quite transcends age. I don’t know her life story yet, except that she was born in the house where she lives, and has lived there her whole life. Her calm gaze seems to be that of a woman who has seen a lot, and come though unscathed. She always looks out for me and Freddie, and I like her very much.